Applying Pascal’s wager to job interview thank-you notes

What I really want to talk about is thank-you notes after job interviews and why I believe you shouldn’t send them – but first, we’ll dive into “Pascal’s wager” to develop the decision framework for later use.

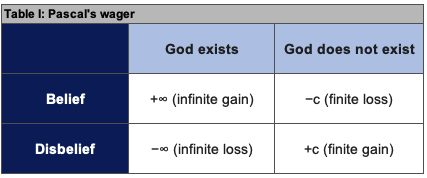

“Pascal’s wager,” named for the 17th-century French polymath Blaise Pascal, is a theological argument for believing in God. (Our interest here is less on the theological side and more on the decision-theoretical side.) Pascal’s wager can be summarized as “even under the assumption that God’s existence is unlikely, the potential benefits of believing are so vast as to make betting on theism rational” [1]. The argument begins with the assumptions:

- Each person can believe in God, or not believe in God. Each person is forced to choose belief or non-belief. (This choice is the “wager.”)

- If God does exist, there are potentially infinite rewards to believing in God (e.g., heaven), and potentially infinite costs to not believing in God (e.g., damnation).

- If God does not exist, the person is no worse off by believing in God or not believing in God.

- The probability of God’s existence must be greater than zero, even if it is infinitesimal.

A rational person will make a choice with the highest expected value (reward). Therefore: believing in God is the rational choice, because the expected value of that choice is infinite according to our assumptions, and the expected value of not believing in God is negatively infinite (eternal hellfire, etc.). This is true even if the wagerer puts a small probability on the existence of God, because a small number multiplied by infinity is still infinity.

To formalize the above: The wager can be summarized with the following decision matrix [2]:

The last column is up for debate. I assume here (because it’s helpful for later) that the combination of “Belief” and “God does not exist” is a finite loss because there are psychic and other costs believing in God (guilt, tithing), though one can easily make the opposite argument that belief in God has net psychic benefits because of the sense of comfort and community, etc. That need not be litigated here; because of the potential for infinite gains or losses, the direction of the finite gains or losses doesn’t change the argument or the mathematical result. This matrix formalizes that belief is the optimal choice because it results in infinite gain, and disbelief is the suboptimal choice because it results in infinite loss.

Anyway – we’re going to move on from Pascal here and onto thank-you notes. There’s a large literature on Pascal’s wager and its counterarguments, and I’d encourage anyone interested to check it out further. Ultimately, I don’t find the argument very compelling (there’s some laxity of language – what does it mean to “believe” in God and why is this something that can be chosen, rather than felt?), but the formalization of this decision matrix is useful. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy cites a source that claims that Pascal’s wager is “the first well-understood contribution to decision theory” [3].

Applying Pascal’s wager to the post-interview thank you note

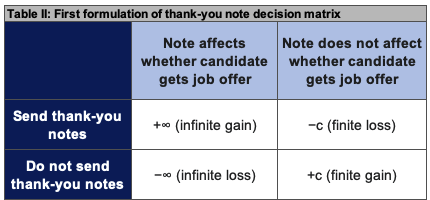

After a job interview, a candidate can choose to send thank-you notes to their interviewers, or can choose to not send thank-you notes to their interviewers. Let’s say the candidate does this in order to increase the chance they receive a job offer, and, for the sake of argument, let’s make the following assumptions:

- Sending thank-you notes to interviewers has a finite cost, because the candidate has to spend time and mental effort.

- Not sending thank-you notes to interviewers has a finite benefit, because the candidate can use that free time how they wish.

- If a candidate gets the job, this job has infinite value.

- If a candidate does not get the job, this result has negatively infinite value.

As we’ve stated the problem now, this is identical to Pascal’s wager. The sending of a thank-you note may or may not affect the interviewers’ decision of whether to give the candidate a job offer, but if it does, it has infinite rewards. See our matrix below:

By similar logic to Pascal’s wager, if the decision matrix above were correct, the candidate should always send thank-you notes.

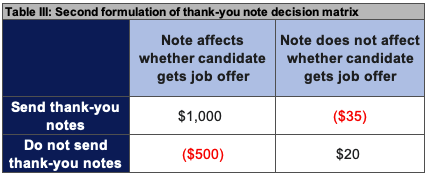

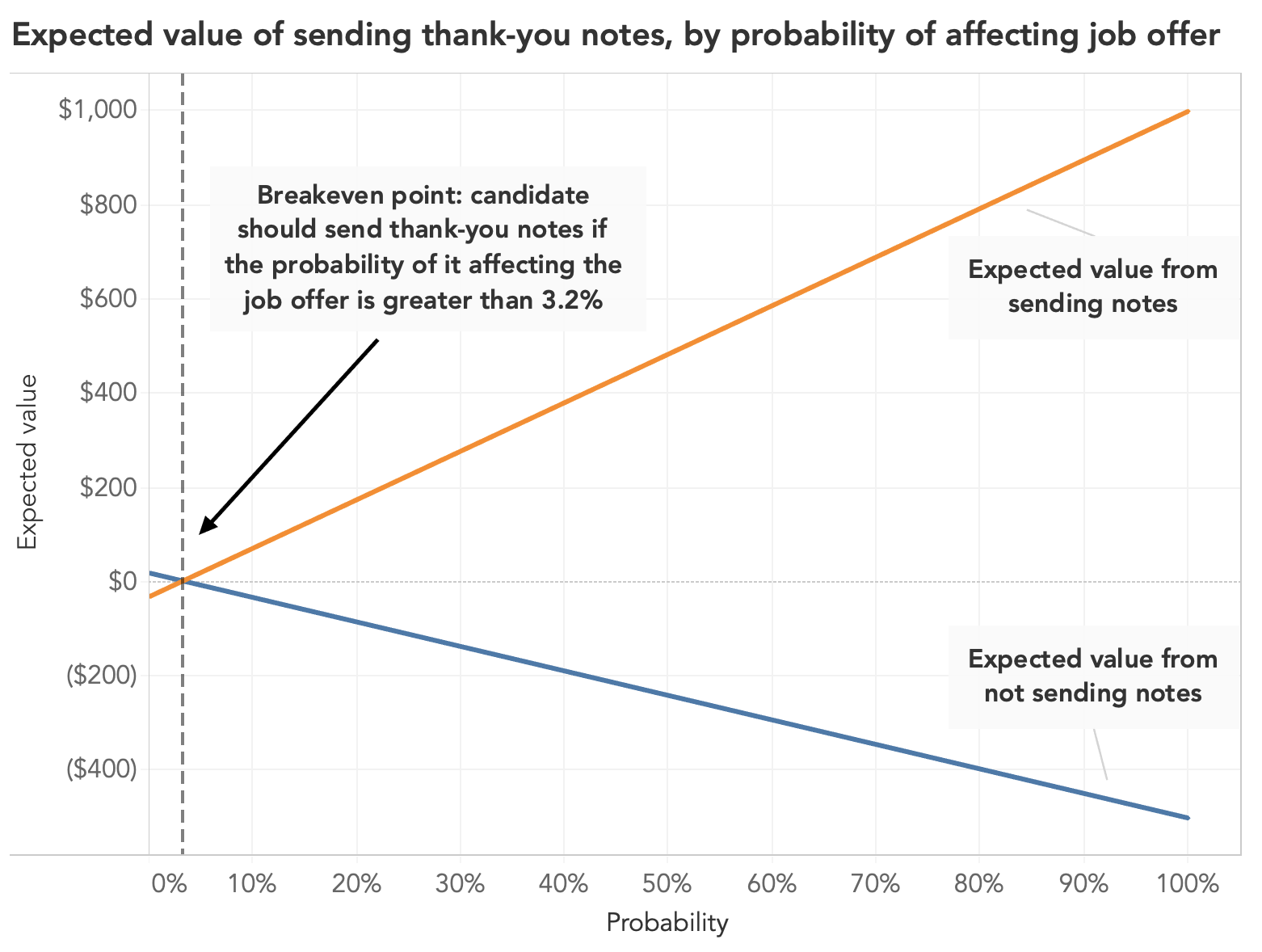

One might raise an eyebrow at the assumptions of infinite utility or disutility from getting the job. Isn’t this extreme? What if there are more jobs out there? Sure, instead we can replace the gains and losses with actual values (converting everything to monetary value):

From these values we can also do some additional math – we can compute whether the candidate should send thank-you notes or not, based on the probability that the notes affect whether the candidate gets a job offer. With some algebra, we can determine that the breakeven probability is 1/31, or around 3.2%. If the candidate believes the probability of sending notes affecting whether they receive a job offer is greater than this, they should send notes.

The curveball

Now that we’ve established the above, time for a curveball: I actually believe that the decision matrices we just look at for whether to send thank-you notes are all wrong, and we have it backwards! The optimal choice is never to send thank-you notes.

My argument rests on one key assumption: If a thank-you note affects whether you receive a job offer, it is not a company you want to work for! A company should evaluate a candidate on their presumed ability to do the job. If the presence or absence of a thank-you note makes any difference in the offer phase, it’s a red flag in regard to the management style of those you’d be working for (e.g., they’d evaluate your performance based on style considerations over substance). Not good. Putting any evaluative weight on thank-you notes also disadvantages any candidates who may not be familiar with that as a professional norm.

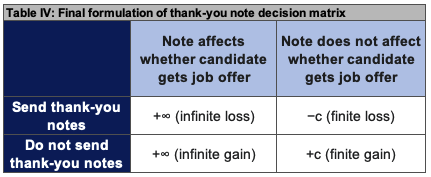

Now let’s re-draw the decision matrix (and we’ll use infinite losses and gains, even though it’s hyperbole):

Now, “do not send thank-you notes” is a strictly dominant strategy, and “send thank.-you notes” is a strictly dominated strategy. No matter whether the note affects the job offer or not, the outcome is always better by not sending a thank you note.

We can impeach the above with a couple caveats:

- There are certain jobs such as Sales where the thank-you note can be considered an additional “audition” for the job because it’s a skill related to the actual role (e.g., written communication with the goal of influencing a decision). In this case it’s more reasonable for an employer to put weight on it.

- This matrix assumes the candidate has absolute discretion in where they want to work and isn’t under any time pressure to take a job for financial reasons. This is a position of privilege that not everyone is so fortunate to have! If it is the case that someone was under some pressure to accept a job offer, we could redraw the decision matrix to more accurately reflect this person’s decision calculus and tradeoffs, and this can result in an optimal choice to send thank-you notes.

All in all, interviewing is difficult from the perspective of the employer (e.g., implementing the right level of rigor to create an interview process with high precision and recall) and prone to conscious and unconscious biases. I won’t fully discuss this here, but one method of reducing bias is to implement a standardized script, question set, or rubric (often the opposite of how many people conduct interviews, who mistakenly believe in their ability to get accurate signal from a free-flowing conversation!). And one simpler, easier way to reduce bias and renew focus on what matters is by ignoring thank-you notes in any decision-making. Or, even better yet, explicitly tell candidates somewhere in the communication process that you won’t consider thank-you notes and there’s no need to send them. “And no, that that’s not a trick, we really don’t want you to send them!”