Solving The Riddler's Tower of Hanoi with Markov chains

This week’s Riddler column over at FiveThirtyEight sets us up with some classic fodder for mathematical puzzles – the “The Tower of Hanoi,” also known as Lucas’s tower. As the column notes, the tower…

… consists of three poles and three disks, all of which start on the same pole. The three disks have different diameters — the biggest disk is at the bottom and the smallest disk is at the top. The goal is to move all three disks from one pole to any other pole, one at a time, but there’s a catch. At no point can a larger disk ever sit atop a smaller disk.

And our puzzle asks the question:

For N disks, the minimum number of moves is (2^N)−1. … But this week, the minimum number of moves is not in question. … With each move, [the player] randomly chooses one among the set of valid moves. … On average, how many moves will it take for [the player] to solve this puzzle with three disks?

To solve this puzzle, we’ll turn to one of my favorite techniques, Markov Chains, which in the past we’ve used to solve Riddler puzzles related to eating chocolates and LeBron James’s 1-on-1 win probability. (Note - we’ll punt for now on the extra credit question which asks for the case of N disks instead of 3.)

The solution we get from our Markov chain approach is 637/9, or about 70.7 moves on average to complete the puzzle. This is over 10x the minimum number of moves (7) required to complete the puzzle.

How did we get there? Below, I’ll walk through my Markov chain approach implemented in Python to solve the problem, and subsequently confirm the result with a Monte Carlo simulation. (Note - we’ll punt for now on the extra credit question which asks for the case of N disks instead of 3!)

State transitions and Markov chains

We can represent the Tower of Hanoi puzzle as a series of discrete states. For example, the game’s starting state has each of the three discs on the same pole. (Let’s assume in our game that we’re starting from the second pole. It doesn’t matter which of the three poles is the starting pole and which are the success poles as the math is the same because we don’t have to move discs onto an adjacent pole. Starting on the second pole saves us a couple lines of code!) For our first move, we might move the top disc from the second pole to the third pole. This represents a new discrete state. The movement that occurred from the starting position to this state is called a transition.

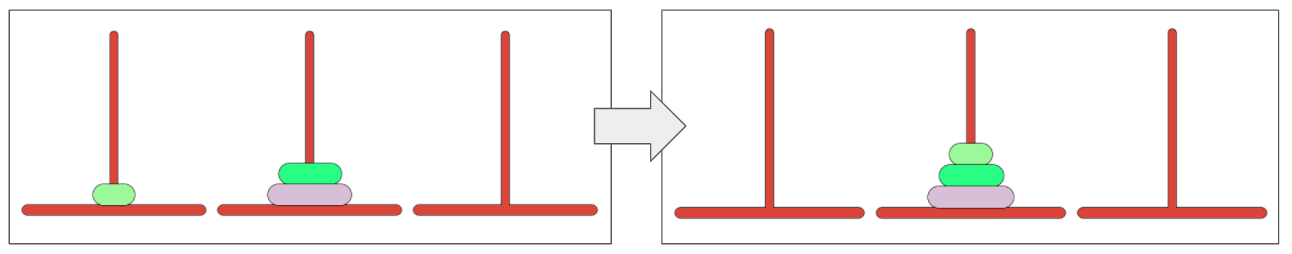

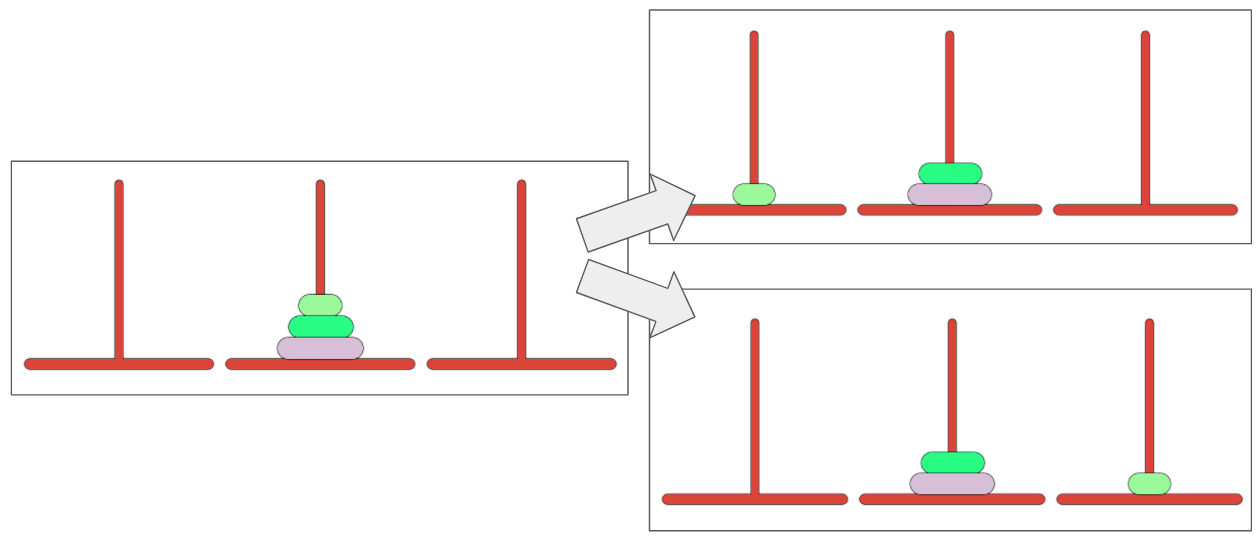

To solve the problem, we’ll need to generate a Markov transition matrix, also called a stochastic matrix. This matrix shows the probability of each state transitioning to each other state. For example, the initial starting state has two potential states it can transition to: moving the smallest disc onto the first pole, or the smallest disc on the third pole, as shown below. The player in our problem will make each of these moves with equal probability. The matrix formalizes which states can transitions to which other states in tabular form, and contains the associated probababilities of transitions.

To help code our matrix, we will give names to all our states. I choose to describe the position of each disc using Cartesian coordinates, where the x-coordinate represents the tower (1, 2, or 3), and the y-coordinate represents the height (1, 2, or 3). We can nest these coordinates into a tuple, where the first position in the tuple will note the coordinates for the largest disc, the second position the middle-radius disc, and the third coordinate the smallest disc. For example:

- ((2,1),(2,2), (2,3)) represents the starting state

- ((2,1),(2,2), (1,1)) represents a potential second state, as shown in the first picture above

- ((1,1),(1,2), (1,3)) and ((3,1),(3,2), (3,3)) represent the winning states (“absorbing” states in Markov parlance), which end the game.

The biggest disc always has to be on the bottom, no matter its x-coordinate, so the y-coordinate for the first set of coordinates will always be 1.

After writing some code (available here) to generate all the valid states and find all the valid transitions between states (this was the bulk of the work), we can draw up our transition matrix.

As it turns out, there are 27 valid states for the game, resulting in a 27 x 27 transition matrix. With the exception of the initial position (which has 2 valid transitions) and the absorbing states, each of the 24 remaining states has valid transitions to 3 other states. Only one of these 3 potential transitions will be the “right” one to draw the player closer to the victory – so on any given move non-starting move, it’s more likely than not that the player makes the “wrong” move!

Solving the problem

In previous Riddler columns where we’ve used Markov chains, we’ve been asked to find the probability of transitioning into each absorbing state. Here, the question is a bit different because we’re looking for the average time (steps) to absorption. Thankfully, once we have our transition matrix, it’s just a few lines of code to get our answer. (Note: while finding the average time to absorption is analytically simple, I don’t know of any methods that allow us to explore the distribution of time to absorption without resorting to Monte Carlo trials. Let me know if this isn’t the case!)

To get our answer, we use some linear algebra and follow the steps to compute the fundamental matrix and and find the expected number of steps. We can do this in just a few lines of code (the variable “matrix” is our transition matrix):

number_of_absorbing_states = 2

I = np.eye(len(matrix) - number_of_absorbing_states)

Q = matrix[:number_of_absorbing_states*-1,:number_of_absorbing_states*-1]

N = np.linalg.inv(I - Q)

o = np.ones(Q.shape[0])

print(np.dot(N, o))

From this, we get that the answer is 637/9, or about 70.7 moves on average to complete the puzzle. I also run a Monte Carlo simulation of 100,000 runs of the puzzle that gives us a similar result.

We’ll need to do some code refactoring so we can also handle the extra credit, but the same Markov framework can be used to solve the general case.

Full code

The full code is available on GitHub.